This is a favorite saying of mine from childhood. My older sister and I—both fans of puns, homophones and subversive humor—said it to each other often, so much so that it became an inside joke apropos of nothing. All she’d have to do is say something inane to provoke me, like profess her love for Big Bird and John Bon Jovi in the same breath, and I’d deliver the blind man line as though I were a psychotherapist and she my crazy patient. Somewhere along the way, we discovered there was a second half to the saying, the part about his deaf wife. “Oh, Santa,” my sister said the first time she heard the complete verse. “You sleigh me!”

Today, when I think of that saying, it’s not my taste for bad jokes I question as much as why sight is so heavily used to communicate understanding in the first place. “I see what you mean,” people say. What? What do they see? Sometimes I wonder if everyone else are able to picture emotions as hi-res spectrals of light, or concepts as complex geometric shapes. Because I can’t. Even when I try, I don’t see see much of anything.

And yet, these insightful metaphors (see what I did there?!) are everywhere. We only believe what we can see, find hindsight to be 20/20, and love shedding light on new thoughts and ideas. Even in my yoga class, we wish each other ‘namaste’ at the end while sitting cross-legged on the floor with our heads bowed to our hearts. ‘Namaste,’ by the way, means “the light in me sees the light in you.”

On the other hand, why wouldn’t we rely on the physical world, and sight especially, to describe our inner world? Of the five senses, sight is the most dominant. According to the National Geographic book in our bathroom, the one I bought for my kids but only I seem to read, sight constitutes up to 83% of our sensory input. Without this bridge to a shared, physical reality, how else are we supposed to describe the ephemeral, ineffable and psychic feelings of the human condition?

Yet.

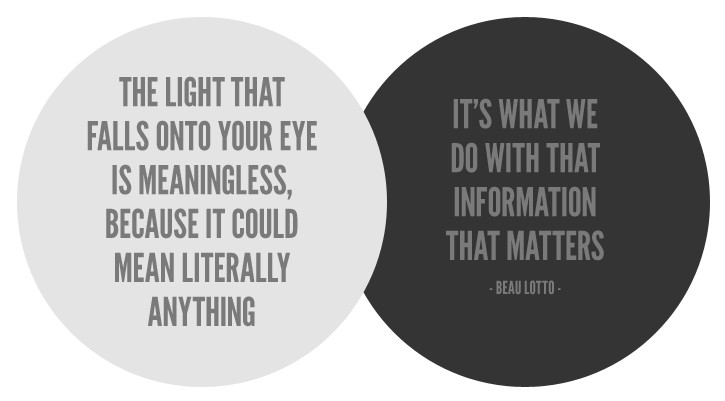

Is it possible that we’ve gotten too attached to these metaphors to the point of losing sight (!) of the underlying mechanics/fallacies? For one thing, we are only consciously aware of a fraction of what we ‘see.’ In addition, raw visual input is chaff until the brain finds meaning in it. Take that dark mass I often spy on the floor of my dining room. Sometimes it’s my black cat, Harry. Other times it’s my husband’s black nylon laptop bag. Still other times, it’s both and I have to do a double-take to figure it out. And don’t get me started on the Internet’s blue and black dress.

So if eyes are fallible and can be tricked, what does that mean for the legitimacy and value in using sight metaphors to convey understanding? Isn’t it also possible that the words we use, on either end of a conversation, are as fragile in meaning and interpretation as what we ‘think’ we see at any given moment? To be as inane as my sister for a minute, what if my friend the blind man was talking to his deaf wife because she liked to read lips? Or was mumbling while signing to his wife? Hell, maybe it was a private joke between them—that he would talk nonsense he knew she couldn’t hear.

I can’t know for sure. Can you?

Silly, I know but the question is: why are we in such a hurry to figure out what others mean to say without confirming or clarifying first? Are we really all that vain to assume we know everything? Or are we conditioned to avoid looking dumb? Maybe if we did slow down, observations would feel less like judgments, arguments more like constructive dialogue and misunderstandings an inside joke.

In the end, we can’t, and don’t, always know what others mean to say to us, regardless of metaphor or words used. We can, however, ask more, listen more and expect more. After all, what you see is what you get.

A really excellent argument for giving others the benefit of the doubt. Really good!

Thanks, Nina!

Brilliant!

Thanks, Kris. :)